One of my favorite (but not used all that much) test item types is the “matching exercise.” One class I teach has quite a bit of vocabulary that my students just flat-out need to memorize. Matching seems like a good, concise way of testing them with a minimum amount of pain on their part (writing the answers) and my part (creating the test).

The sources all agree on the definition:

A matching exercise consists of a list of questions or problems to be answered along with a list of responses. The examinee is required to make an association between each question and a response.

I was pleased to see this same source describing the types of material that can be used:

The most common is to use verbal statements… The problems might be locations on a map, geographic features on a contour map, parts of a diagram of the body, biological specimens, or math problems.

Similarly, the responses don’t have to be terms or labels, they might be functions of various parts of the body, or methods, principles, or solutions.

This other source, http://teaching.uncc.edu/learning-resources/articles-books/best-practice/assessment-grading/designing-test-questions, lists

- terms with definitions

- phrases with other phrases

- causes with effects

- parts with larger units

- problems with solutions

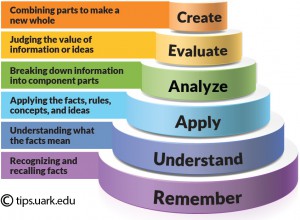

As you can see, this test item format is well-suited for testing the Knowledge Level of Bloom’s Taxonomy, however several sources hint that it can apply to the Comprehension Level “if appropriately constructed.”

Only one source discusses in detail how to “aim for higher order thinking skills” by describing variations that address, for example, Analysis and Synthesis. (http://www.k-state.edu/ksde/alp/resources/Handout-Module6.pdf)

One variation is to give a Keylist or Masterlist, that is information about several objects, and have the student interpret the meaning of the information, do comparisons (least/greatest, highest/lowest, etc.), and translate symbols. The example gives three elements from the periodic table with the properties listed below them but no title on the properties. The questions ask “Which of the above elements has the largest atomic weight?” and “Which has the lowest melting point?” and other similar inquiries.

Another variation is a ranking example:

Directions: Number (1 – 8) the following events in the history of ancient Egypt in the order in which they occurred, using 1 for the earliest event.

These directions are followed by a list of events.

While I see these variations more as the “fill-in-the-blank” types, their connections to matching properties to objects or events to a time line make it reasonable to treat them as matching types.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of matching exercises?

(Source: http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/writing-good-multiple-choice-test-questions/)

These questions help students see the relationships among a set of items and integrate knowledge.

They are less suited than multiple-choice items for measuring higher levels of performance.

(Source: http://www.iub.edu/~best/pdf_docs/better_tests.pdf)

Because matching items permit one to cover a lot of content in one exercise, they are an efficient way to measure.

It is difficult, however, to write matching items that require more than simple recall of factual knowledge.

Maximum coverage at knowledge level in a minimum amount of space/prep time.

Valuable in content areas that have a lot of facts.

But

Time consuming for students.

There are design strategies that can reduce the amount of time it takes for students to work through the exercise, and others that don’t put so much emphasis on reading skills. We’ll look at those in the next post.

Recent Comments