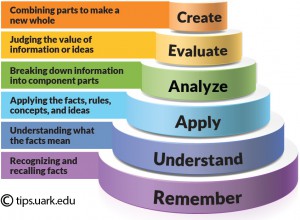

*Graphic from http://tips.uark.edu/using-blooms-taxonomy/

It is often thought that multiple choice questions will only test on the first two levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy: remembering and understanding.

However, the resources point out that multiple choice questions can be written for the higher levels: applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

First, we can recognize the different types of multiple choice questions. While I have used all of these myself, it never occurred to me to classify them.

Source: http://www.k-state.edu/ksde/alp/resources/Handout-Module6.pdf

Types:

Question/Right answer

Incomplete statement

Best answer

In fact, this source states:

…almost any well-defined cognitive objective can be tested fairly in a multiple choice format.

Advantages:

- Very effective

- Versatile at all levels

- Minimum of writing for student

- Guessing reduced

- Can cover broad range of content

Can provide an excellent basis for post-test discussion, especially if the discussion addresses why the incorrect responses were wrong as well as why the correct responses were right.

Disadvantages:

- Difficult to construct good test items

- Difficult to come up with plausible distractors/alternative responses

They may appear too discriminating to students, especially when the alternatives are well constructed and are open to misinterpretation by students who read more into questions than is there.

So what can we do to make multiple choice questions work for higher levels of Bloom’s?

Source: http://www.uleth.ca/edu/runte/tests/

To Access Higher Levels in Bloom’s Taxonomy

Don’t confuse “higher thinking skills” with “difficulty” or “complicated”

- use data or pictures to go beyond recall

- use multiple choice to get at skill questions

Ideas:

- Read and interpret a chart

- Create a chart

- “Cause and effect” (e.g., read a map and draw a conclusion)

Another part of this source brings up the idea of using the “inquiry process” to present a family of problems that ask the student to analyze a quote or situation.

- No more than 5 or 6 questions to a family

- Simulates going through inquiry process, step-by-step

- Identify the issue

- Address advanced skill of organizing a good research question

- Ask an opinion question (but not the student’s opinion)

- Analyze implicit assumptions

- Provide for a condition contrary to the facts, “hypothesize”

This source gives some good ideas, too.

Source: http://www.k-state.edu/ksde/alp/resources/Handout-Module6.pdf

Develop questions that resemble miniature “cases” or situations. Provide a small collection of data, such as a description of a situation, a series of graphs, quotes, a paragraph, or any cluster of the kinds of raw information that might be appropriate material.

Then develop a series of questions based on that material. These questions might require students to apply learned concepts to the case, to combine data, to make a prediction on the outcome of a process, to analyze a relationship between pieces of the information, or to synthesize pieces of information into a new concept.

In short, multiple choice questions, when designed with good structure and strategies, can provide an in-depth evaluation of a student’s knowledge and understanding. It can be challenging to write those good questions but the benefits are worthwhile.

I thought about writing a summary of what we have learned about multiple choice questions but found this funny little quiz to be better than anything I could come up with:

Can you answer these 6 questions about multiple-choice questions?

Recent Comments