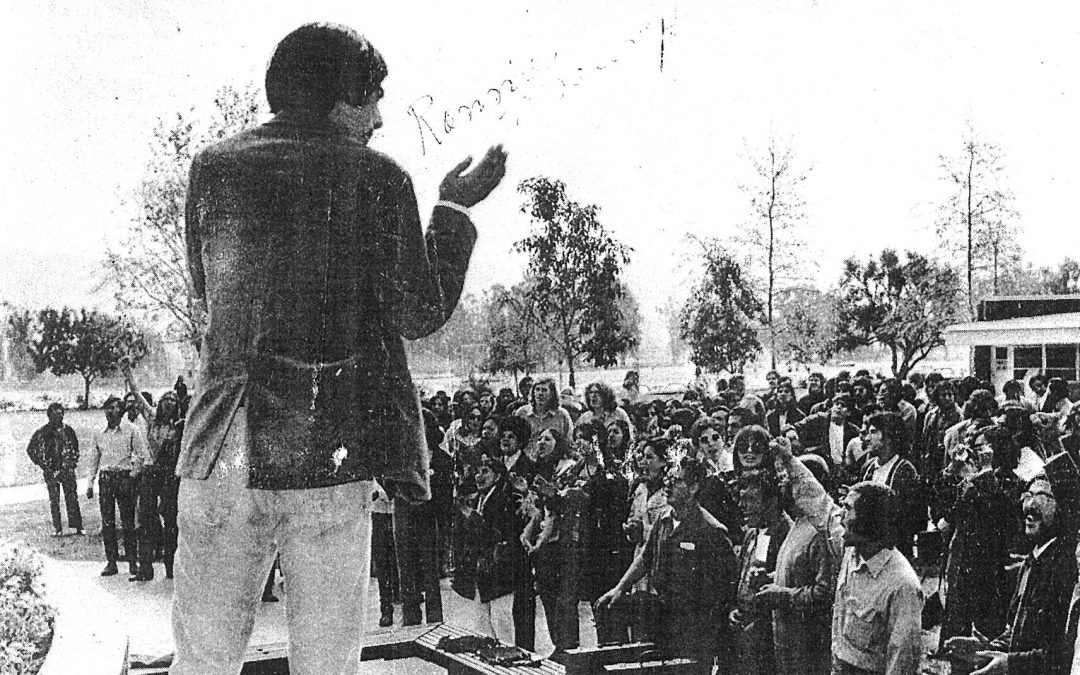

Pictured above: Nearly 50 years ago, students gathered for a demonstration on campus to push for academic reforms. In the foreground, Rolando Moreno, a M.E.Ch.A. leader, speaks to the assembled protestors.

Early efforts to resist and overturn institutional racism at Palomar College focused on bringing minority and oppressed voices into a whitewashed curriculum.

SAN MARCOS — In the late 1960s, a surge of student activism at Palomar College brought the first wave of reforms that may now be understood as antiracist, challenging a system that had not acknowledged or dignified non-white people in any of its curriculum.

College records and interviews with those who were part of the movement show that it was the establishment of a handful of academic programs and the efforts of student groups like M.E.Ch.A. (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan) that began to turn the tide of systemic racism at Palomar.

First came the formation of a pioneering Multicultural Studies Department, in 1971, which included three distinct areas: Africana Studies (AS), Chicano Studies (CS) and American Indian Studies (AIS). The latter would become its own department by the end of the decade.

Latino, Black and indigenous people “had been left out and not given a fair chance in schools,” Paul Jacques, the first Chair of the Multicultural Studies Department, said at the time. “Most history books have very little information about minorities.”

But that was beginning to change at Palomar College.

“With all of the upheaval and progress happening today, it’s easy to lose sight of the invaluable work that previous generations of students, faculty, and staff did to oppose the racist systems they inherited,” said Interim Superintendent/President Dr. Jack Kahn.

“Our story of antiracism begins, appropriately, with institutional changes that meant Black, Indigenous, and People of Color would be represented directly within the academic disciplines for the first time at Palomar College,” added Dr. Kahn.

Chicano Studies

In what would become a pivotal moment in the history of Palomar College, some 200 people gathered on campus in March 1971 to demonstrate for the expansion of the fledgling Multicultural Studies program.

The crowd included students from Palomar, but also from SDSU, UCSD, several other community colleges in the area, and supporters from M.E.Ch.A., a student organization founded in 1969 to “promote Chicano unity and empowerment through political action.”

Among the protestors that day was a young UCSD graduate student named John Valdez.

“Really, this begins with the student movement—we were strong, organized and fearless,” recalled Valdez, a M.E.Ch.A. officer at the time. “It was an era of student protests. We were struggling for education, for the farm workers, for the end of war in Vietnam.”

The specific demands presented to Palomar’s leadership at the student rally that day centered on the hiring of new faculty to support Multicultural Studies.

In a March 1971 article in The Telescope student newspaper, Jacques was quoted as saying, “We’re interested in lifting our people out of the dregs of society where they have been placed. The classes will not be attended by Chicano students only. The classes are actually for the better understanding of the Chicano culture by white students.”

The rally that day left a deep impression on Valdez, who recalled the deafening silence of nearly all of the Palomar College administration except for one man, Theodore Kilman, Dean of Community Services.

Valdez would return the following year in search of a job and stay on as a faculty member at Palomar for 42 years until his retirement in 2015.

He recalls the 1970s and 1980s as a period when Chicano Studies struggled for legitimacy within an institution filled with contempt for the growing field of multicultural studies.

“There were a lot of struggles, a lot of tension within the campus community,” said Valdez. “No one ever told me directly to my face, but I would hear comments: ‘We’re bringing in the ghetto, bringing in the barrio, we’re going to bring the institution’s standards down.’ We were suspect because we were part of this movement, yet we had gone to all the universities they went to, had the same degrees they did. But somehow, we weren’t as qualified as they were.”

Still, recalled Valdez, “We weren’t going to let these comments dissuade us. We knew our purpose there was to teach, to inspire, to educate, to advance our cause on campus and in the community. It evolved, little by little, one class at a time.”

Valdez recalled that several Palomar employees, including English Professor Gene Jackson and Engineering Professor Bill Bedford, were key mentors and supporters of the student movement. He also remembered fellow M.E.Ch.A. leaders Alejandro Paz, Carlos Encinas and others as crucial to the effort to establish Chicano Studies at Palomar.

He also recalled one of the college presidents of that time, Dr. Frederick Huber, as being an early ally when most of the faculty was against the idea of creating or expanding Chicano Studies.

“Dr. Huber could talk to the students, negotiate with the students, and he opened the door,” said Valdez. “He was very enlightened, open-minded compared to the others, and under his leadership, M.E.Ch.A. had an active role in talking and negotiating.”

American Indian Studies

During the late 1960s, a group of students with ties to local American Indian tribes organized a chapter of the Native American Student Alliance at Palomar College. The beginning of American Indian Studies as an academic discipline at the college “came about primarily through student protests—they camped in the president’s office and pressured the school into responding to the lack of their presence on campus, and the lack of a curriculum,” recalled Patti Dixon, who has taught at Palomar since 1971 and is the current AIS Department Chair.

“Our students were using the tools of the time, which were protests,” said Dixon, a member of the Pauma Band of Luiseño Indians. “They were saying, ‘Why should we not have this? We are important too, and there are things you should know about us.’”

Added Linda Locklear, who came to Palomar in 1974 and is a Professor Emeritus in the department: “California has the largest number of Indian reservations in the United States, and San Diego has the most of any county in the United States.”

In response, the college created the first two courses representing Native American people on campus: California Indian History and Lifestyles of North America.

Locklear, who comes from the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, recalled that “some of our biggest opponents were other faculty. For a few years, it was always a big fight to survive.”

“We called it academic bigotry, and it was very strong in certain departments,” said Steven Crouthamel, another Professor Emeritus in the department who started in 1975.

Crouthamel recalled experiencing, for decades, what are now known as microaggressions—common daily interactions laced with a thinly veiled tone of superiority: “You would be talking to somebody and you’d hear them saying, basically, you were not up to their level. And the courses were considered lower-class or not as academically sound.”

Like their colleagues in Chicano Studies, AIS faculty had to jump through extra hoops to legitimize their discipline, and got used to weathering institutional pressures and attacks that other departments never experienced.

But slowly and painfully, Crouthamel and Dixon recalled, the department earned its right to exist.

In the late 1990s, there was a global movement to include indigenous people in higher education curriculum, and leaders from around the world started showing up at Palomar to learn from its AIS Department, which had been one of the first in the U.S. when it was created in the ‘70s.

“We were successful in our strategies. We understood that we had to win over our faculty, who had a very conventional idea of what should or should not be taught as history,” said Dixon. “We’re sort of the vanguards, making sure that the story is more than one vision. We offer depth to the story of being American.”

Looking Back, Looking Ahead

All things considered, Valdez says, it was a shift in the student population that made the difference in igniting a lasting change at Palomar: “Students were breaking the stereotypes of being sedate and accepting—our students were activists. They had never seen anything like this before; students weren’t going to be pushed around.”

When he looks back on his 42 years at Palomar, Valdez says he realizes just how far the institution has come. “I think it says a lot that we’re here, that we survived. A lot of people would have liked us to go away, fade out.

“I would say the leadership is outstanding, we have good faculty, and there’s a whole lot of talent in the department. They have their hearts and minds in the right place—serving the students,” Valdez added. “Even though, in the early days, they may have seen us as illegitimate, the door was open. We came in, tried to do our best, and I think what we have today is a testament that we were successful.”

This is part two of a series of stories examining the history of antiracism at Palomar College. Subsequent stories will appear on Palomar News, and in the index below, as they are published.

SERIES INDEX

1. Introduction and Story Index

2. The Early History of Antiracism at Palomar College (current page)

3. Opening the Campus Doors to Marginalized People