Funded by an $800,000 National Science Foundation grant, Palomar College will expand course offerings and establish a Certificate of Achievement in unmanned aviation.

SAN MARCOS—On any given day with a clear sky, professional drone pilots are scattered across San Diego County, controls in hand, taking aerial photos of construction sites, inspecting power lines or peering into the nests of endangered birds.

Experts say the civilian applications of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are virtually endless—and it’s still early for an industry that is expected to generate more than $80 billion of economic impact and 100,000 new jobs in the coming years.

This summer, Palomar College expanded its groundbreaking UAV program with a three-year, $800,000 grant from the National Science Foundation. The grant allows Palomar educators to begin offering a UAV Certificate of Achievement with a focus on entrepreneurship, explained Dr. Wing Cheung, the program’s co-coordinator.

Across industries, the technology “is disrupting the way we have traditionally done our work,” said Cheung, who teaches Geographic Information Systems (GIS) at Palomar. “In my field of mapping and analysis, drones have made data collection much quicker, cheaper, and also much more real-time.”

From preparing student UAV pilots to pass the Federal Aviation Administration licensing exam to training them to think more entrepreneurially, Palomar is on the cutting edge of civilian UAV training in San Diego.

Jesse Gipe, Manager of Economic Development for the San Diego Regional Economic Development Corporation, said that Palomar’s approach is likely to pay off for the various industries that stand to benefit from drones.

“We like what Palomar is doing with this program, because they’re thinking not just about the technology, but also about the business applications, which are critical,” said Gipe. “It’s not just, ‘Can I fly or build a drone?’—which are both great things. But what are you going to go do with it? That’s where the value is.”

The sky’s the limit

The popular perception of drones is typically associated with warfare or photography, and the program’s other coordinator, Mark Bealo, is a Graphics Communication instructor at Palomar who uses UAVs as a photographer. Sharper, cheaper images from the sky probably will remain one of the chief benefits, but experts in a variety of fields are increasingly relying on drones.

“You can think of drones as a tool, like Microsoft Excel, which you can use to keep track of your personal expenses, or to do complex analysis,” Cheung explained.

Bealo rattled off a list of industries, from roof inspections to farming to search and rescue, in which drones are already making huge leaps in safety and efficiency.

“There are all of these opportunities to implement the technology in various industries, but a lot of people in those industries don’t know about it,” Bealo said.

That gap in expertise has always been a driving force behind Palomar’s UAV classes, which have been ahead of the curve since the beginning. When he was filing the paperwork to establish college’s initial drone curriculum in 2014, Bealo recalled, the chancellor’s office informed him that it was the first curriculum of its kind in the state.

Making better maps

For Cheung, the initial attraction was that he could use UAVs to collect far better data for his GIS classes than what was publicly available online.

“As a geographer, making maps, oftentimes we get a very big-picture view of the Earth,” said Cheung. “We use satellite images as the background for a lot of our maps, and these satellite images (tend to be) very outdated, or coarse in resolution.”

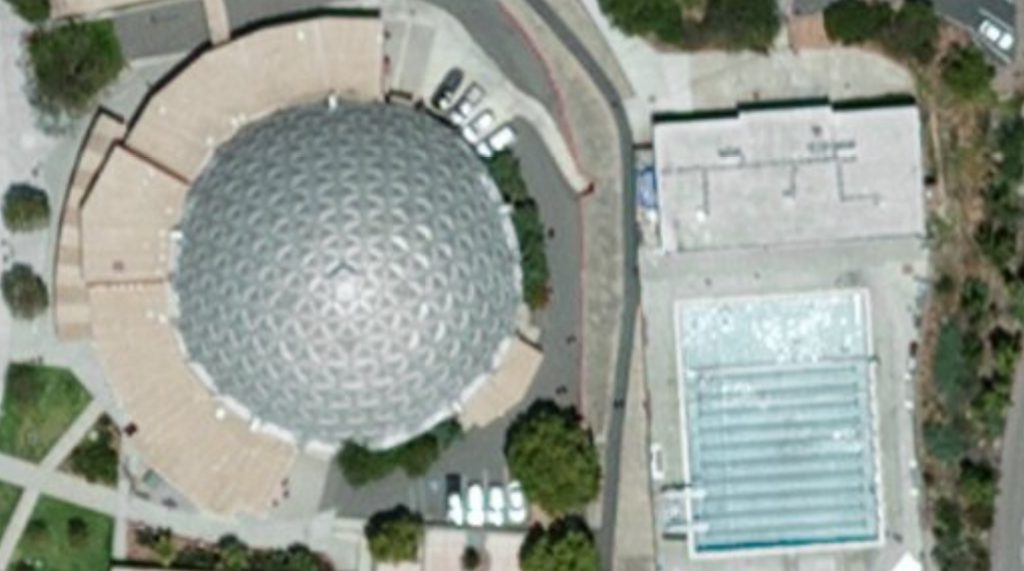

An aerial view of the Palomar College Dome and swimming pool, taken using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Credit: DigitalGlobe, Microsoft, Mark Bealo, Wing Cheung

The publicly available satellite image of the same part of campus. Credit: DigitalGlobe, Microsoft

For example, the size of each pixel, or “cell,” in many NASA or USGS satellite images is 30 meters tall by 30 meters wide. “In an aerial photo that may be shared by a local agency like Sandag, cells would be six inches by six inches,” he said. “With your own drone, you can collect aerial photos with cells that are two centimeters by two centimeters.”

Previously, that kind of resolution was only available by paying airplane or helicopter operators to take the images—a luxury that Cheung characterized as “incredibly expensive.”

In the end, drones won him over because of the promise they held for geographers: “The prospect of having your own platform for collecting real-time data and using it as part of your map or part of your analysis—that was mind-blowing,” said Cheung.

A safer, more efficient tool

Last year at SDG&E, Hector Ubinas began overseeing drone flights. Previously, UAVs were considered part of the utility’s research and development, but then it became clear how powerful the technology was going to be.

Ubinas is SDG&E’s Aviation Services Manager, a job that has traditionally revolved around helicopter operations. While helicopters are still central to utility work, Ubinas said drones have quickly become an indispensable tool. “We are constantly looking for use cases for the drones,” he said.

For example, when inspecting new construction, SDG&E will frequently use drone-mounted Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) sensors to verify that a new power line was built according to specifications. “In the past, it was all done on the ground, with a crew of four or five people,” recalled Ubinas. “It was very time-consuming, because they’d have to set the sensor, take the measurements, hike in and out. But now we can do it in a matter of an hour or less, and we’re getting really good data with the bird’s-eye view.”

The utility also uses drones to perform some routine power line inspections. Any time they can use a drone, Ubinas said, they save time and dramatically reduce the risk of worker injury because they don’t have to send an employee hiking or climbing.

While SDG&E has staff who are fully qualified to operate drones—Ubinas included—he said the company does not employ any dedicated drone pilots, and contracts out the more specialized work to local companies.

“The LIDAR takes special expertise, so we go to the outside vendor who does it on a daily basis,” he explained. “We’re going to have a lot of highly specialized applications that require more than just taking pictures.”

Regional economy set to benefit

While UAV technology is just beginning to make inroads in most markets, drones have been an important part of San Diego’s economy for years. The defense industry here has done huge business in military UAVs: Both the Predator and the Reaper, deployed in the War on Terror, are produced in San Diego by General Atomics, and the Global Hawk, a large unmanned spy plane, is built by Northrop Grumman based on research done by its San Diego engineering team.

Gipe, the economic development expert, said that real estate, agriculture, utilities and construction are all industries in need of more drone operators. Even in the defense industry, “There’s a growing demand for cheaper systems that can be deployed rapidly, with less concern if they get shot down or break. We see every branch of the military thinking creatively about how to use swarms of cheaper drones.”

Part of Gipe’s job is to anticipate how the UAV industry will mature—and what resources it will need as it grows. Topping the list: Qualified operators.

“We are very much believers that talent drives industry growth in any particular cluster,” he said. “Without access to the right talent pools, industries are constrained in their ability to grow. The industry is rapidly evolving, but having people who are trained and can think creatively about the technology is going to be a benefit.”

Cheung said many businesses who rely on UAVs—like SDG&E—prefer to contract drone work out to third parties rather than maintaining their own UAV staff in-house.

“That’s why we included business and entrepreneurship classes in this certificate that we’re building, so we can train not only drone operators, but drone entrepreneurs,” he said. “They may start a small company where they offer drone services to local Realtors or the local TV station, or local governments that don’t have the resources to do their own drone data collection.”

Ubinas, who along with Gipe serves on the college’s Unmanned Aircraft System advisory board, said he is excited about Palomar’s growing program.

“I think it’s awesome that this program has taken flight,” said Ubinas. “I see the need for the technology just growing in the future, and we’re going to want to have access to experts who know what they’re doing.”

A bright future

Like the technology itself, Palomar’s UAV program has developed with breathtaking speed. The first drone-related class at Palomar College—Digital Imaging with Drones—was introduced four years ago; just last year Cheung and Bealo launched the UAV program offering one of California’s first college certificates in drone technology.

Spurred on by the NSF grant, they will now be able to offer a broader range of classes—a total of 11 to earn the Certificate of Achievement—and train more students in a technology with immense potential in the local economy.

Cheung said they hope to have 30 students enrolled in the program at any given time, with different tracks to accommodate varying interests: “If they’re interested in designing and maintaining drones, they’ll go into the engineering track and take engineering classes. Or if they’re interested in doing mapping and surveying with drones, then they’ll take my set of GIS classes. If they’re interested in videography and filming, then they’ll take Mark’s classes.”

Cheung and Bealo are also hopeful that they can persuade other educators of the value of UAVs. If the drone program partners with other departments at Palomar, a student could add a drone certificate without switching majors to stand out in their field after graduation.

Learn more about the drone technology program at Palomar College.

Read about the grant on the National Science Foundation website.