The term artificial intelligence (A.I.) has been floating around the world of technology and pop culture for decades now, but what was once speculation or science fiction is now a reality.

A.I. has rapidly progressed its capabilities and skill set and can perform tasks on a level that is human-like. With this rapid progress comes a growing concern from people in technology, education, and the general public. But the question now is, what exactly are people’s concerns with A.I. and are they valid?

Brief history of A.I.

The eventual rise of A.I. has been speculated and theorized since the 1950s following the invention of the computer. The development of A.I. has been a long and strenuous journey, but now it has become commonplace in our everyday lives. Everything from the shows and movies that our favorite streaming service recommends to us, to the autofill text feature on our phones and computers is provided by A.I. But now, the capabilities of A.I. are reaching a point that was previously only imaginable.

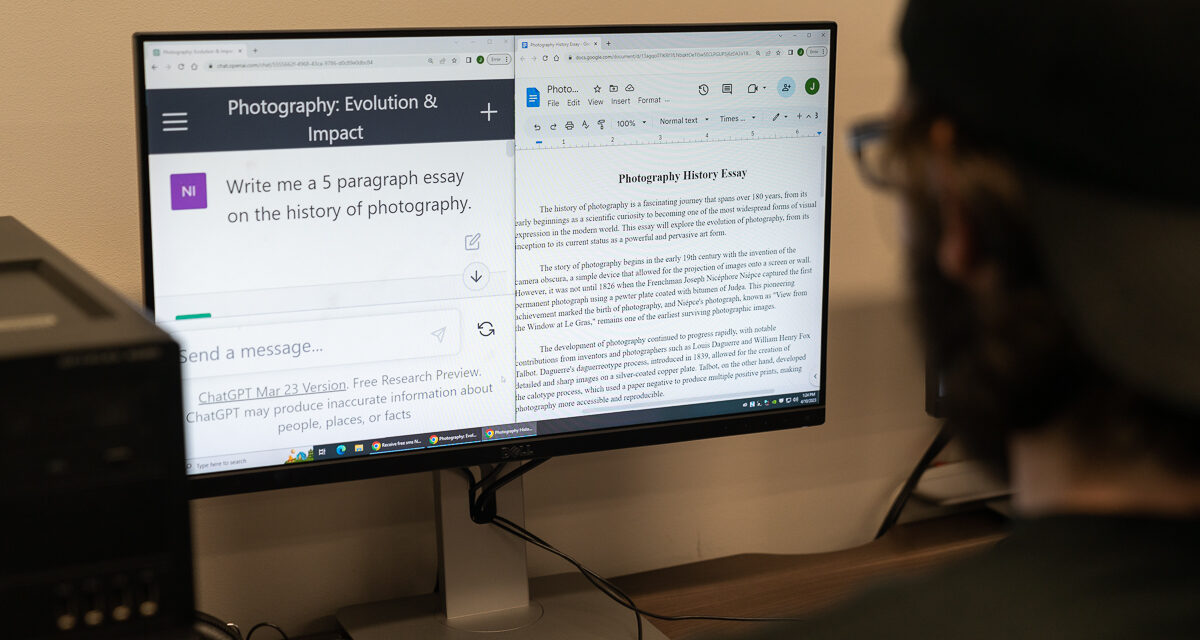

Current A.I. programs and tools, like ChatGPT, can write a 1,000-word essay on just about any topic you can ask it and can create images so lifelike you’d think it was real at first glance. And this development has been a rapid one, which has caused some concern.

Just recently, a letter was published calling for a 6-month pause of A.I. development which was signed by leaders of the tech industry, such as Steve Wozniak and even Elon Musk. Italy also recently banned the popular A.I. tool ChatGPT from processing Italian users’ data. And now, it must be asked if A.I. tools like ChatGPT will see any more bans in other countries or even in schools and universities.

Why the concern

A lot of the concern, coming from both people who work in the field of technology and from policy makers, could pose a possible threat to the development of A.I. technology. Whether or not the concern on the matter is valid is still up for debate, as well as the reason why these people are calling for bans and restrictions.

“It’s very possible that this is the next computing revolution, so if you look at the Internet, then you look at mobile [phone], this could be the next one. It could be basically widespread high-functioning A.I. or human interoperable tools,” said Professor Bryan Donyanavard, a computer science professor at San Diego State University. “I think whatever this category is of A.I. tools definitely could be the next revolution. If the tech is legit, which it seems it definitely is, this won’t be the highest-impact application. This is like the source; this is like the kernel of what we’ll see over the next decade of people taking it and just running and doing stuff we haven’t even thought of yet.”

Someone else who spoke on the matter was Mahyar Salek, the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) and co-founder of Deepcell, a biotech company based out of Menlo Park, Calif. Deepcell uses A.I. and machine learning in a microfluidics platform to image, identify and isolate cells to be researched and tested on. “So, my background is in computer science. I did my Ph.D. in algorithms, and that sort of morphed into A.I. and machine learning when I realized that there’s a lot you could do more if you have access to data,” Salek explained on our Zoom call.

He discussed the possible reasons as to why there is so much concern about the state of A.I. and why Italy banned ChatGPT., “I think what we are seeing right now is human nature, you know, this is a disruptive product or disruptive API, and human nature when you are faced with something disruptive, one of the natural reactions would be avoiding it,” he said.

“I hope we come to a realization that whether we like it or not, we are at the point of no return. Meaning, this is a technology that now we have, and we better understand it, regulate it, and put guardrails around that rather than banning them.”

CTO of Deepcell Mahyark Salek poses for a picture in the outdoors of Menlo Park. (Photo courtesy of Deepcell)

A.I. in academics

Another concern is whether an A.I. tool like ChatGPT should be allowed in schools and universities. Professor Donyanavard spoke on whether hethinks there should be any limits on how students use A.I. in schoolwork.

“I think philosophically, from a teacher’s perspective, we should as a whole be thinking about what are we assessing,” he said. “Are we assessing skills and outcomes in the best way possible? Like, I don’t give exams in any of my classes, and that’s just because I don’t think that’s the best way to assess the skills.

“I think the best way to try to tackle this challenge of what’s basically, you know, plagiarism, or cheating, or dishonesty using tools, I think we have to think the same way about, like maybe our methods need to change, right?”

“I think philosophically, from a teacher’s perspective, we should as a whole be thinking about what are we assessing. Are we assessing skills and outcomes in the best way possible? Like, I don’t give exams in any of my classes, and that’s just because I don’t think that’s the best way to assess the skills.” ~ Professor Bryan Donyanavard (Photo by Di Huang)

A student’s perspective

Professor Donyanavard isn’t the only one who feels this way about the use of A.I. tools in schools and universities. Ben and Alex, who requested to have their last names left out, are currently using A.I. in their university studies. Ben, a student at UC San Diego is currently majoring in cognitive science.

“Definitely classwork, I would say like bigger assignments, I will use it as like a tool rather than as like, ‘just give me the answer,’” he said. “I feel like A.I. is really good for helping you learn if you know how to use it correctly. And it’s just where you start to abuse it is where you get into hot water.”

It’s also important to understand what factors determine whether or not students use A.I. to help them.

UCSD student Ben smiles at the camera while he works on his laptop before going to class. (Photo by Griffin Norwood)

“Whether it’s busy work or not, right? So, if it’s repeating an action, or if it’s something that takes a long time, but it’s not necessarily, like, a task that takes a lot of brainpower. So rather than just having to put a lot of time into it, I’ll use A.I. to kind of shorten it to minutes,” Ben said.

He also added when he will not use A.I. “Definitely essays, like, think straight up essays or big assignments. I think the simplest thing is just don’t cheat yourself out of improving yourself, whether that’s learning or whatever it is, like, it’s a slippery slope, and you got to know how to play it.”

Alex is a business administration major at Mt. San Jacinto College. Because of scheduling conflicts, he spoke over text. “I started to use A.I. tools in January. I use these A.I. tools in my class work if I ever need little help grasping a certain concept, and when it comes to my daily life I have asked it (ChatGPT) to write me an effective gym schedule based off my current goals and situation,” he texted.

When asked whether or not he thinks A.I. tools should be allowed in school settings, he responded, “I do personally believe that they should be allowed in school and universities to an extent, but if students will just use it to cheat and essentially not learn then my answer would be no but I do believe it can be used to help add to research.”

Salek also shared similar thoughts. “I don’t think there’s anything unethical about using the latest technology. It might look unethical for a while because not everybody knows about it and can access it,” he said. “But as soon as there is wide access, there is wide awareness of what this is and what this can do, it will be the status quo.” •

While A.I. can generate realistic-looking images, it still has its shortcomings if you look closely. (Alex Ortega/The Telescope)

Recent Comments