Deaf culture has transformed its cultural legacy.

But what does it mean to be deaf?

“My whole life is surrounded with the Deaf. This is me, I’m Deaf. It makes me who I am,” Cheryl Ravitch said, a Deaf Advocate and Referral Specialist at Deaf Community Services of San Diego.

Ravitch now wears cochlear implants, which is a device surgically placed on a person’s cochlea in order to allow partial hearing.

“I was born hearing, but I took medication that caused me to turn deaf,” Ravitch said, adding, “I wore hearing aids from age 4 until I was 19 years old, when they stopped working. So from 19 years old until 32 I was completely deaf.”

She explained how the Deaf have proudly reclaimed their identity and even the word “Deaf.”

“You have a (lowercase) ‘d’ which means, I am just deaf, and then you have the big “D” which means, my fiancé is Deaf, I work for the Deaf, I advocate for the Deaf, this is me,” she added.

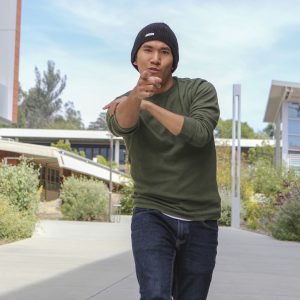

From a hearing perspective, we may see a world of silence, a life of limitations and language barriers. Perhaps the Deaf see bridges instead of barriers. “We have imperfections and that’s what makes each of us unique, knowing that we can overcome whatever’s thrown at us and that we learn from that experience makes us even more of a better self than before,” Angelo Ricasata said, a Cal Poly Architectural Graduate and American Sign Language (ASL) Lab Tech at Palomar College. Ricasata had a premature birth that caused deafness that deteriorated before getting cochlear implants.

On a deeper level we might feel that with deafness we would lose our identity, our culture, our language. This assumes that your identity comes from a balanced, healthy culture, but does it?

Do we measure Beethoven or Helen Keller’s intelligence on what language they use?

Photo by Aubree Wiedmaier/Impact Magazine

“Everything almost appears to me in an artistic form, you know? But we see things differently, collaborate in other ways; we have our own history too, and our own language and fine arts,” Antoine Hunter, Founder of Urban Jazz Dance Company and former director of The Bay Area Black Deaf Advocate explained. Hunter is completely Deaf in his left ear and hard of hearing (HOH) in his right ear.

In their struggle to define themselves the Deaf have even reclaimed the word “deafness” which only describes a person’s static medical condition. The Deaf prefer the term “Deafhood” relating to people’s process of finding and actualizing themselves in the hearing world.

Is a person’s social currency based solely on his ability to speak?

With resiliency, openness, and collectivism the Deaf continue to define their culture on their own terms.

“I believe Deaf culture is a forest of people who are proud of their roots. It is the power of our roots that allow us to grow strong,” Hunter said in an interview with KQED. Hunter’s words denote a wisdom shared with Matthew Moore one of the authors of “For Hearing People Only,” quoting, “The Deaf soul experiences the restrictions, prejudices and hostility of the hearing world so that it may progress to a higher level of spiritual understanding.”

The World Health Organization says there are over 466 million people in the world with hearing loss. This is over 5 percent of the world’s population. While the medical society has 4 categories of deafness ranging from mild (able to hear normal conversation -greater then 30 decibels) to profound (can only hear very loud noise like standing close to a train -greater than 90 decibels).

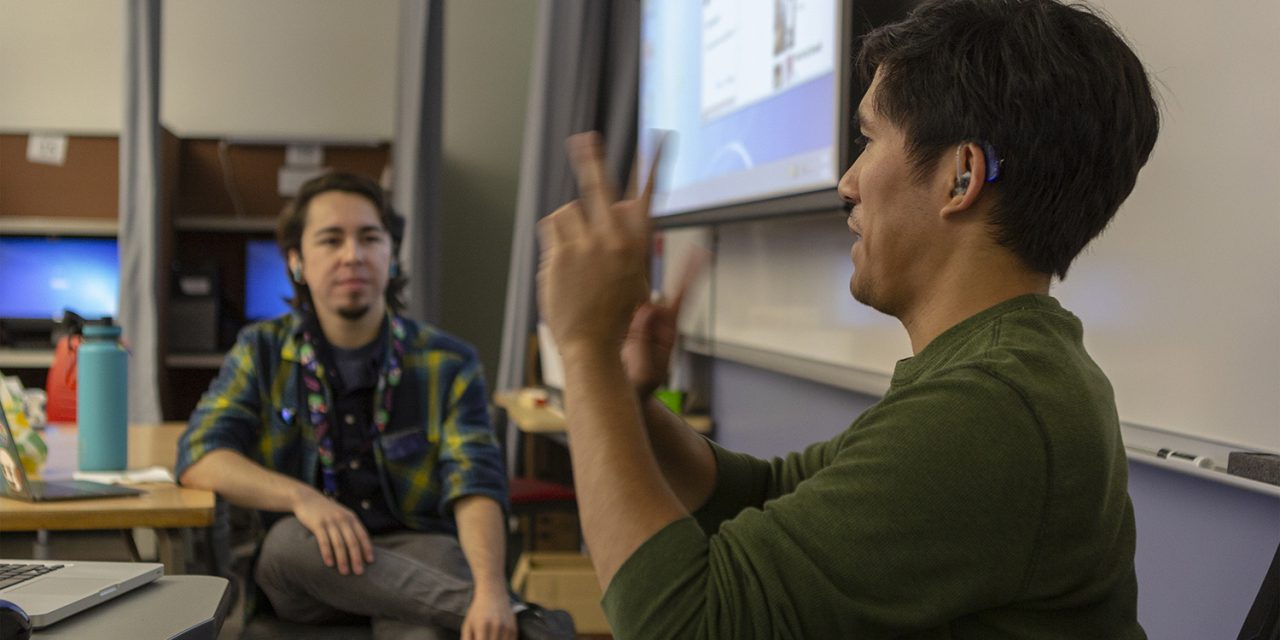

Photo by Aubree Wiedmaier/Impact Magazine

ASL is the 4th largest language in North America. Sign Language has over 200 dialects existing in the world. For much of history ASL was

not classified as a language, only in 1960 was it academically recognized as a language minority.

For centuries the Deaf have strived to reframe the mainstream narrative and perception about what it is to be whole, what it is to be different and what it means to be labeled disabled. “Yes, people have often labeled Deaf individuals as handicapped, or ‘broken,’ which is really presumptuous. It’s really such a negative word… For me, being deaf is a way to see and hear with my eyes the world differently,” Hunter said.

Aristotle claimed that since the Deaf lacked speech they were incapable of reason or abstract ideas and banned them from Greek schools. In early Christianity the Roman Church excluded the Deaf based on the Apostle Paul’s Epistle “Faith cometh by hearing and hearing by the word of God.”

The renaissance saw growth as scholars and clergy in Spain and France were successful in teaching the Deaf through writing and early sign language. Then the Eugenics movement of the 1890s and one of its leaders Alexander Graham Bell pushed for Oralism (speech and lip-reading) over sign language. “It caused a lot more damage thsn it helped,” said Lawrence Morris, a Hard Of Hearing Veteran and Palomar College Communications major.

The Eugenics/Oralism movement punished and separated the Deaf in hopes of assimilating them into society, calling sign language primitive and even un-American to not speak English.

Bell even discouraged Deaf intermarriage and suggested sterilization.

Just as colonists relabeled Native Americans as Indians for centuries, the Deaf have also been classified by the hearing world.

By the 1960s ASL was recognized as its own unique language. The harmful Oralist education practices and treatment were exposed and proved unscientific and could no longer be justified, but the concepts die hard.

“It (ASL) was discouraged by my doctors because I still had some residual hearing,” said Ricasata, who is also a Choreographer and dancer that joined Hunter in a “Deaf and Dance” fundraiser for Deaf and Hard of Hearing (HOH) youth in San Diego schools.

OPENNESS

The inquisitive and open heartedness of the Deaf is not just out of necessity to build their network, but also a built-in characteristic to absorb and convey as much information as possible. “We miss so much, so any input is great,“ said Morris. Like any social being they seek connections, and being open and flexible to react to so many forms of communication is not just survival instinct, it’s their identity. “It’s more that to be deaf is to be human with a different way of adapting to life. If it were not for those adaptations we wouldn’t have gotten this far,“ said Ricasata. The Deaf welcome members no matter where they sit on the continuum of deafness. There are some members who only lip-read and some that only can finger-spell out words; they all pitch in to help each other.

The Deaf cherish communication, eye contact and are acutely aware that they cannot access the majority (hearing) culture if the majority is not willing. “Their willingness, the Deaf culture is extremely open, they are very welcoming, it’s just like any other culture it’s what you make it,” said Deaf and Hard of Hearing teacher for Carlsbad High School Jamie Pemberton. Also since some Deaf communities are very small they must use all resources available from any source. Perhaps a byproduct of being open is the heightened awareness. Where the hearing may feel that silence is isolating or empty- the Deaf may see it as an opportunity to process and absorb subtle, visual, non-verbal cues. Perhaps the lack of hearing allows the Deaf to cut through the small talk, to cut through the politeness of speech going straight to the simple truth of who they are and what they want.

They are also very open to different styles of communication. Many Deaf people use videophone apps like Facetime or Skype to communicate or even texting apps like Signily that translate words into ASL symbols. “We are not time oriented, we are people oriented,” said Ricasata.

Thirsty for details, their storytelling can be exaggerated just to extend the shared time together. Body language, expressions and posture add texture, context and flavor to their long stories and extended goodbyes. “Yes, we take awhile to say goodbye and then we say goodbye again, we try to stop but we are very social,” said Ravitch. By being open and adapting Antoine Hunter has created more opportunities for all artists not just Deaf to express themselves. “The San Diego Deaf and Dance Festival is an opportunity for local San Diegan Deaf performers and artists to showcase their talents through various mediums, whether be it paintings, choreography, and the likes,” said Hunter.

Deaf artists like David French (sculptor of the Lincoln Memorial) as well as physicists; micro-surgeons and Pro-athletes have defied the notion that speaking is equated with intelligence.

COLLECTIVISM

The Deaf community shows a spirit of collectivism as they work together to maximize the strength of the whole community. This action counters the Oralist-Medical model that denied the Deaf an equal worldview on social and political policies. They are typically centered in community centers or schools with Deaf services. It seems like a paradox in the way they embody both with collectivism and the independence to operate inside a hearing world that for so long did not recognize them. “My dance performance was about breaking the ice to start up a conversation about different issues that goes on in the world, both good and bad.” said Hunter. By using art, Antoine can break down the perceived barriers of language so the hearing people see the dancer, the athlete, and the human behind the social mask of a Deaf person. For that split second we see bridges instead of barriers, we see ability rather then disability. We are oblivious to our conscious or unwitting phonocentricism (belief that speaking and hearing is equated with intelligence). Where we saw separation now we see connection. This opens the window to see our shared story, a shared connection and shared issues.

“I talk about rights and language acquisition, diversity, societal discrimination, social injustice and Women’s rights,” added Hunter.

His efforts have brought attention to Deaf advocacy all over the world.

Palomar student Cecelia Cheung working on a piece of art in the glass blowing class at Palomar College. Photo by Aubree Wiedmaier/Impact Magazine

“In Hong Kong there was a lot of things that I wasn’t able to do, yeah it was a lot of negativity you are in the deaf group or in the hearing group, there is no mixing, there is no mainstreaming,“ said Cecelia Cheung, a Palomar College Art major and VONS clerk who was born Deaf and grew up in China.

We’ve been to so many countries and formed many wonderful relationships, like people from London, India, Peru, Colombia, Brazil, etc. Seeing all these Deaf dancers in a space where we feel safe and yet be able to express ourselves in art is simply indescribable. We learn so much from them wherever we go,” said Hunter.

We do have International Sign, but regardless of the differences in our sign languages, we were able to bond immediately, because of our life experiences in the hearing world said Zahna Simon, another dancer and member of Urban Jazz Dance Company.

Yet with the residual effects of Oralism and Audism (the belief that the Deaf are inferior) and the fragmented policies on education and assimilation it would seem hard to build cohesion. “So you are finding yourself in conflict at a fork in the road, finding conflict with where the middle ground is, somewhere where the Deaf American culture can become a hybrid if you will, because at this point there is no hybrid” said Ricasata. Examples of a hybrid bilingual community have appeared in history such as Martha’s Vineyard in the 1600’s as well as parts of the nobility class of the Ottoman Court (Turkey). In these societies sign language was highly valued and respected as a positive cultural value.

The issues of access, support, planning, development of watchdogs, role models and advocates for Deaf and HOH children, women, and elderly in hospitals, prisons or schools will continue.

Perhaps the western, individualistic ideology that built the idea that one language, one culture or one identity (hearing or Deaf) is superior to another will erode. Author Paddy Ladd states that, perhaps the atomistic view of deafness will be replaced with Deafhood, a positive value that does not need to be cured like a disease. “They (doctors) don’t understand that it’s a cultural thing within us. We just embrace ourselves. It’s beautiful, it’s our language. From an audiology perspective they want to fix it. That’s fine, but it would be best if they provide all the information instead of just trying to fix it,” said Ravitch about cochlear implants being promoted by hospitals.

By affirming their community and their differences without the need to dominate or subvert the forces that created those differences, the Deaf transform their identities. If I lost the gift of sound, would I miss the train’s horn, the crash of the waves, the sound of my breathing?

Maybe, but I could still feel the rumble of the train, still sense the wind on my skin and still be aware of each exhale. Perhaps I can be an ally to Deaf instead of part of the cultural vacuum they experience.

Instead of the perspective of clinging to a cliff, perhaps being Deaf can be standing on a bridge and each language can meet in the middle, the only limits we put is on ourselves. As the poet Rumi said, “Silence is the language of god, all else is a poor translation.”

Recent Comments