People often confuse archaeology with paleontology. And few know what archaeology even is nor do they consider it a possible career option. While paleontology explores life through organic remains like fossils, plants, and bacteria, “archaeology is the study of the human past, usually through material remains,” said Archaeology student Blake Georgouses. So, archaeologists might dig up things, but no, they don’t include dinosaurs.

Palomar Archeology professor Elizabeth Pain explained that “our job is to identify historic activity areas and structures, which aren’t documented. So that’s what archaeologists do; what is not documented we can try to find through archaeological excavations.”

About the Program

The Palomar College Archaeology Program was established 45 years ago and features a wide range of classes and resources designed to give students the technical skills they need to go straight into the field. This could be a job with a CRM (Cultural Resource Management) company, a state park, or a museum.

The Telescope spoke with three current and former Palomar students and learned about their experiences in the program, which offers an associate’s degree and a 1-year Field Technician Certificate. Pain recommends that students just do both, since many of the courses overlap, and it would only require a few additional ones.

Blake Georgouses began at Palomar in 2017 originally to study biology. But after working at the San Diego Natural History Museum, he became fascinated with archaeology and started taking classes in the subject. “I ended up at Palomar because very few community colleges give you actual access to archaeological sites. So we got actual field experience. Like right off the bat.” he said in a Zoom interview with The Telescope.

According to Pain, the program was ranked by Universities.com as one of the best hands-on field programs in California in 2018-19. Palomar College is likely the only community college in San Diego that offers an excavation course where students get to do field work at live archaeological sites.

Right now, students in the class are excavating at the Rancho Penasquitos Adobe in Poway, CA, where they have been for the past 12 years. The adobe was built in 1824 by Captain Francisco María Ruiz and is one of the oldest residences in San Diego. They visit the site on Saturdays from 8 am to 4 pm in small groups of around three or four and dig.

“We excavate a unit together,” said Georgouses, “which is just like a meter by meter square, typically. But it’s at an active archaeological site. So, this isn’t just like a hole in the ground. This is an actual archaeological site that we’re excavating.”

He describes some of the things found at the site, which include metal artifacts, glass bottles, ceramics, animal bones, leather parts, and a brick with paw prints in it.

Along with the professor, there’s typically an advanced student present at the site who has taken the course before. They help give instruction and guidance during the excavation. “So it’s a full day, but it’s a really fun experience and you know, you when you’re in a small little hole with three other people, you get to know them very well very quickly,” Georgouses joked.

One Field, Three Paths

Since graduating from Palomar in 2019, Georgouses received his BA from Cal State Fullerton and has just begun working on his master’s degree at San Diego State University, “but I’ve been taking Palomar classes the entire way through my bachelor’s and master’s,” he explained, “because they have classes that are specifically geared to the professional field.”

Sue Hagen has a bachelor’s in literature and writing from Cal State San Marcos and a master’s in linguistics from Fresno State. “I was at Palomar 22 years ago,” she explained, “and they were doing archaeology digs on campus. And so I would see them as I walked by on my way to class and that looked really cool. But I had this plan; I was really focused.”

She returned to Palomar to study archaeology, adding that it was in the back of her head for 20 years. She completed the program at the end of 2021 and is currently a grad student at Cal State San Bernardino, in applied archaeology. “My plan hopefully is to work for an agency, so something like National Park Service or California State Parks or Bureau of Land Management,” she said.

Ajeng McCunney began at Palomar in 2016 where she studied Art History and then got her BA in the same subject from UC San Diego. “I had initially been a part of the archaeology program then but I ended up switching my major to art history. And so when I came back to Palomar last year, I came back to the program again,” she explained.

She returned to Palomar to get a degree in Archaeology after discovering a graduate program offered by NYU, which combines Art History with Archaeology. “So what I hope to do with that is to become an archaeological conservator. So any materials that come in from an archeological excavation I would work at, cleaning it, preserving it, you know, if it’s broken, putting the pieces together, basically do anything that we can to make sure that it lasts generations into the future.”

Digging Overseas

Georgouses and McCunney both had opportunities to visit other countries during their studies. They shared their experiences with The Telescope and described how archaeological fieldwork procedures change according to geographical surroundings.

McCunney explained that a retired Archaeology professor, Phil de Barros, visits Togo, Africa almost every year to excavate at different sites. He usually brings a small group of Palomar students with him and she was one of those students last year.

“It was a very unique experience. And I’m very glad that I did it. It was it really put things into perspective, which I wouldn’t have had if I hadn’t done it,“ she said. “That particular dig was focusing on mortuary patterns. They’re trying to figure out, in this particular site, was it a family burial? Because we were finding jewelry so if they were being buried with jewelry, were they a higher class?”

McCunney also completed a summer program in which she excavated at a building site in Ireland. With Professor Pain’s help, she was able to find a travel scholarship to help her afford the program. “It’s a great experience to see how excavations are done in other countries because it’s vastly different,” she said.

“How we’ve been taught in the excavation course is when we dig, we dig in units; they can range to various sizes. And we have a context of where things are found. So at certain depths, you’ll find something and you know, if you find something at a similar depth, you can assume it’s from approximately the same time period as long as there hasn’t been any disturbance.”

McCunney explains how the excavation process was different on her trip to Ireland, than how she’d been taught at Palomar. Because the site was on a hill, digging in units would not be very efficient. “They were doing it by context of essentially features of the building. So, we would have a wall, that would be one context. We would have a collapsed wall inside the building. That would be a separate context. So it’s basically done by feature. And then whatever is found in association with that feature, is how it was recorded.”

Early this year, during his last semester at Cal State Fullerton, Georgouses was offered a chance to do a final analysis in Nicaragua. He fondly described his experience of flying out of the country for the first time. “I get on this crowded plane on New Year’s, the whole flight is speaking in Spanish and they hand me a cup of wine, and then we’re off. To celebrate New Year’s, like it turned midnight as we’re on the tarmac. And then we drank the really gross cheap wine and then we left.”

“I was there for two months,” he continued. “And so what I was doing out there is the first month I was excavating on Ometepe Island. It’s an island in the largest freshwater lake in Central America. It’s Lake Nicaragua. And so I was living on that island. For about a month we would ferry on and off the island.”

He excavated at a site thought to be an ancient cemetery, and found remains of about 13 human bodies, as well as jewelry, and pottery, with its bright colors and patterns still intact. Some of these artifacts were dated as far back as 3000 years.

During the second month, he worked at the National Museum of Nicaragua analyzing the excavated remains and writing his report. “So I was analyzing all sorts of different things: turtles, deer, rodents, one… I don’t know about this, but one potential monkey because there are monkeys there,” he said. His report was then published in one of Nicaragua’s national journals. “It was really cool. It was really, really cool.”

Palomar’s Persistence

What makes Palomar’s Archaeology program so great is the number of dedicated professors eager to see their students succeed. “They’re invested in us. Going beyond Palomar, they want us to succeed in the field. They want us to be really knowledgeable about everything when we start working or when we continue our education,” said Hagen.

“There are companies in San Diego, who specifically look for Palomar students because of the experience that we’ve had with our archaeological field class,” she added.

Pain explained that they work directly with the community to find out exactly what skills students need to learn in order to get a job in the field.

“It’s honestly been absolutely amazing. It’s the best college experience that I’ve had,” McCunney said. “Our professors are ridiculously devoted to helping us get as many opportunities as we can. Through Betsy Pain, I was able to find a bunch of different volunteer opportunities that I’m able to put on my resume to hopefully get me into the graduate program.”

McCunney volunteers at The Kumeyaay-Ipai Interpretive Center, and The San Diego Archaeological Center. She is also the President of Palomar’s Anthropology club.

“I don’t think people realize that it’s a degree you can actually do,” stated Georgouses. “because you see it in movies you know, Indiana Jones or somewhere like The Mummy. I didn’t think that was even a possibility of a career.”

“It’s hard work, but it is amazing getting to dig up stuff and being like, ‘oh my god, this is so old. This is so interesting.’ Getting to preserve the past and learn about it and know that I can actually make a career out of this; I can make enough money to live decently and you know, actually get to do this as not just a passion but a career as well.”

Pain’s biggest message to students is “if you want a career in archaeology, you can have a career in archaeology. And we can give you a lot of the hands-on tools, here at Palomar and also the guidance.

Image Sources

- an orthomosaic: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- Michael-John Smuts, certified drone operator: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- working on site: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- Excavation class of fall 2021: Keith Klipfel

- Karakorum Ruins: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- working on site: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- visiting locals: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- student working on site: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- Ger: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

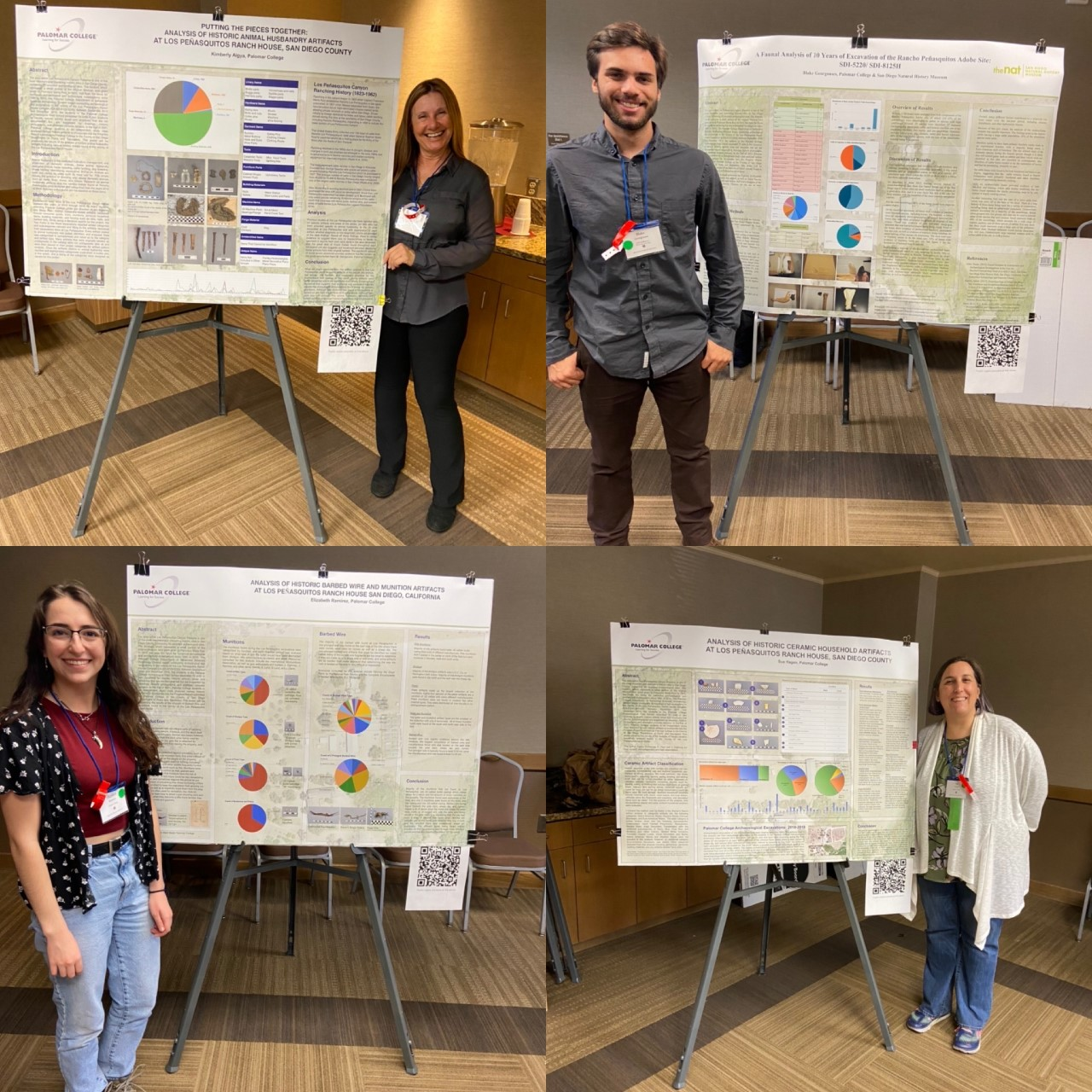

- Students Presents Their Independent Research: Photo courtesy of Prof. Elizabeth Pain. | Used With Permission

- Excavation class leadership team: ElizabethPain | Used With Permission

- surveying: Keith Klipfel | Used With Permission

- the fit: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- bringing out the big guns: Elizabeth Pain | Used With Permission

- students on site: Photo courtesy of Prof. Elizabeth Pain. | Used With Permission

- students on site: Keith Klipfel | Used With Permission

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.